Acoustic Telemetry 101

Acoustic telemetry is the process of measuring biologically relevant data for aquatic animals using transmitters called electronic tags. The tags are externally attached to the animal or, in the case of some fish species, implanted internally. The tags emit acoustic signals at fixed intervals that are detected by underwater hydrophones called acoustic receivers. The type of information obtained via acoustic tracking relates primarily to the animal’s geographic location, but can also include position in the water column, environmental data such as salinity and temperature, and biological information such as acceleration. There are two basic types of acoustic tracking: passive and active.

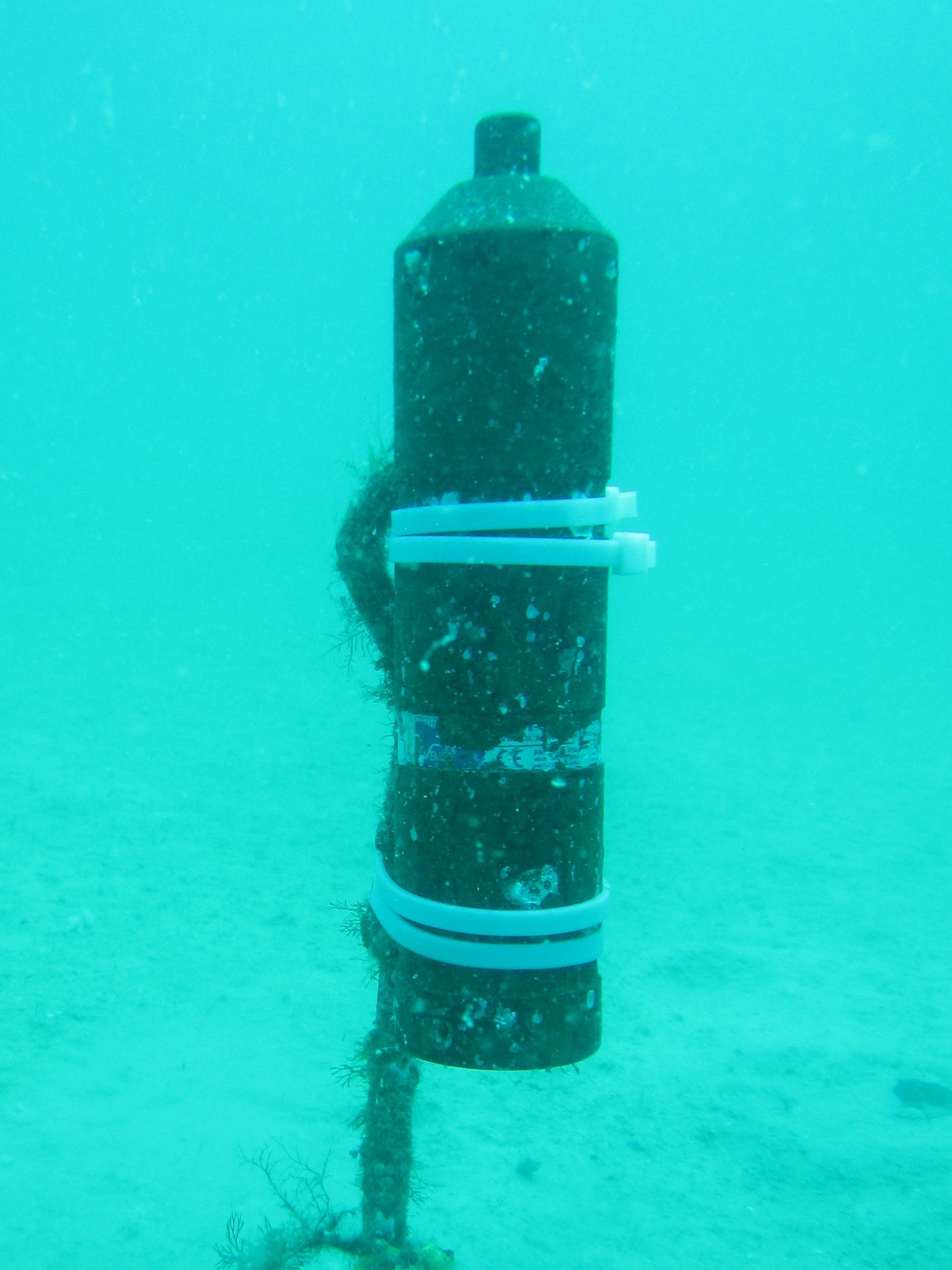

Example of an acoustic receiver (left) and tag (right)

Passive Tracking

Passive tracking occurs via receivers that are anchored fixed in space. Researchers place a number of receivers underwater (called a receiver array)—along migratory corridors, throughout a nursery or breeding area or in other areas that enable them to gather information about fish behavior, movement patterns, habitat use, and survival. Whenever an acoustically tagged fish swims within the detection range of a receiver, its presence is recorded on that receiver in the form of a code unique to that fish, along with time and date of detection. Detection ranges are strongly influenced by environmental conditions and background noise and are generally on the order of a few meters to over a kilometer. Tag batteries typically last from several months to 10 years. The data that are stored on the receivers must be physically downloaded which can be time and resource intensive.

Active Tracking

Researcher engaged in active tracking.

Active tracking consists of using a portable receiver to follow a tagged fish around in real time (usually from a boat) for short periods (typically 1 to 3 days). This is a labor-intensive and exhausting process for the researcher, but it provides more detailed information on fish movement, behavior, and habitat use than what might by obtainable from passive tracking. Active tracking can also be used in pilot studies to help determine the best placement of a fixed receiver array.

Acoustic telemetry is the type of biotelemetry predominantly used by the iTAG community, but it is not the only type. The illustration below gives an overview of biotelemetry technology and shows where acoustic telemetry fits in. More information about the other types of biotelemetry can be found below.

Movement Studies at the University of Florida

Movement is an essential behavior of living organisms—from the wind dispersal of seeds to the multi-basin migrations of bluefin tuna—as such it plays an important role in ecosystems and our ability to develop effective conservation and management. However, for most species we do not yet understand the causes and consequences of movement. Scientists at the University of Florida are conducting research to better understand these processes. Below we highlight just a few of the labs conducting tracking studies at UF but expect to add more in the near future:

The MabLab is led by Mathieu Basille, Assistant Professor in Landscape Ecology. They study spatial ecology inside out, from large-scale patterns using niche analyses to fine-scale mechanisms based on movement ecology. Using a combination of state-of-the-art quantitative frameworks and applied questions, the MabLab investigates the determinants of distribution and home ranges of raccoons, migration and nesting of wood storks, or navigation of seabirds on the open ocean.” lab website: https://mablab.org/

Within the Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Department, Dr. Bill Pine tracks Gulf Sturgeon, amongst other species to assess their spatial fidelity and factors affecting their survival, as well as reproductive timing and spawning site selection. He also uses movement data to better understand the habitat use of native fish in large regulated rivers to improve conservation through work with dame operations. Lab website: https://sites.google.com/view/floridariverslab/home?authuser=0

The MERR lab (Movement Ecology and Reproductive Resilience) is led by Sue Lowerre-Barbieri, who has a joint appointment with Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (FAS/SFRC) and the Fish and Wildlife Research Institute (FWRI). The lab is currently studying movement ecology and reproductive resilience of Red Snapper, Red Grouper, Greater Amberjack, Red Drum, and Gag Grouper. Tracking studies, integrated with other methods, assess how reproductive behavior and source dynamics affect life cycle patterns; year class strength and recruitment; and vulnerability to stressors and fishing. Lab website: http://sfrc.ufl.edu/people/faculty/lowerre-barbieri

The Behringer Lab focuses on marine and disease ecology and is led by Donald Behringer, Associate Professor. Don has a joint appointment in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (FAS/SFRC) and the Emerging Pathogens Institute. He uses passive and active acoustic tracking to study movement in decapod crustaceans (e.g., lobsters and crabs), with a focus on understanding how disease affects their movement and the spatial connectivity of host and parasite populations. Lab website: http://behringerlab.com/

The Nature Coast Biological Station (NCBS) is collaborating with FWRI on a project to evaluate habitat use and movements of Common Snook in an expanding range of the Cedar Key region and Lower Suwannee Estuary. Thus far we have tagged snook over three years and have evaluated their movement throughout the region, with the iTAG data exchange allowing collaboration with USGS members who have detected our snook in the Lower Suwannee River. Future proposed work includes: a comparison of Red Drum and snook habitat use, working closely with iTag members. NCBS website: https://ncbs.ifas.ufl.edu/